The Storyteller: Photojournalist Mario Tama

9 Share TweetMario Tama is an award-winning photojournalist for Getty Images who has covered world events such as Hurricane Kathrina and Pope John Paul II’s funeral. Find out what it’s like to travel to parts unknown and his take on the future of photojournalism.

1. Hello Mario! In a few words, please introduce yourself.

I’m a staff photographer for Getty Images currently based in New York City. I studied photography at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in upstate New York before starting my career at the (now defunct) Journal Newspapers in suburban Maryland. I then freelanced primarily for the Washington Post and Agence France-Presse (AFP) in Washington, DC, before moving to New York City in 2001 to join Getty Images. Since then, I have photographed 9/11, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Hurricane Katrina, the funeral of Pope John Paul II, the U.S. Presidential elections, the earthquake in Haiti and Superstorm Sandy, among other things.

2. How did you become interested in photography?

My father and grandfather were both into photography. I was fascinated with the old b/w photos and films my grandfather had taken in Ecuador and Europe. My father was also constantly taking pictures and allowed me to play around with his Polaroid camera when I was probably 10 years old. I was fortunate that my high school had a photo program with full darkroom, and I bought my first SLR when I was 14, with money saved from being a delivery boy for the Washington Post. In that job, I would see the newspaper fresh off the presses every morning before dawn. After delivering papers on my route, I would have an hour or two to kill before going to school, so I read the Post religiously- It definitely hooked me on journalism. I initially thought I might want to be a landscape photographer, but after attending RIT and being exposed to the work of photographers like James Nachtwey, Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Carol Guzy and Sebastião Salgado, I decided I wanted to document people, not landscapes. It seemed more challenging, more interesting, more unpredictable.

3. What is the most rewarding part of your job?

I feel blessed to be able to travel the world and experience the kaleidoscope of human existence. I do my best to raise social awareness through my images and that is quite rewarding, when I hear people speak about how my images have affected them, or enlightened them a bit in some way. I hope my photographs from New Orleans, for instance, assisted, in some small way, with raising awareness and funds to rebuild. But there is simply no way to quantify the impact of images, and that is often frustrating for those of us in this field. It often leaves us asking questions- What are we accomplishing? Has my work provided real benefit? To see your photograph on the front page of a major newspaper or magazine remains a thrill, but really it is the photographic experiences themselves that provide the deepest reward. To be able to connect with folks on the opposite side of the globe, to witness their struggles and their triumphs, that is the real thing, to document reality head on and hopefully raise awareness. I recall a group of wonderful folks in Canada who started a fund for an orphan I photographed in Haiti after they saw his picture in their newspaper. Those are the best rewards.

4. Describe a typical day in your life as a photojournalist.

There is not a typical day in the life of your average photojournalist and I’m no exception. I really prefer it that way. This is not the profession for someone who enjoys a routine. Truth be told some days are quite boring. Other days are amazing. Some days are filled with love. A few are terrifying and a significant number are mired in sadness, or tragedy. Some days are like a dream where you feel extremely lucky to be doing what you love. This job exposes one to the entire range of our humanity..

5. You often travel to places that are under war or victims of natural disasters, how much planning goes into those trips?

If it is an ongoing war, often we have time to get ready and these preparations can take weeks or months. I’m very lucky to work with some amazing editors. We work hand in hand to do vigorous background research on all the major stories we cover. We also have very detailed discussions with other journalists on the ground, NGO’s working in-country, government officials, translators, drivers, fixers –any contacts we have in the region.

If it is a natural disaster, for instance the earthquake in Haiti, we had photographers boarding planes within a few hours. In those cases most photojournalists have a basic “go bag” ready, and you supplement it with what you can, depending on the location. In other cases, for instance hurricanes, I might have up to a few days to prepare, as was the case during Sandy, when we knew a number of days out she was likely approaching New York City. We monitored the storm track religiously and positioned photographers throughout the region before the storm hit. With hurricanes, you have to arrive beforehand, and you need to be packed with enough food, water, batteries and other supplies to make it through at least a week. Afterwards, there is a decent chance the devastated areas will be impossible to access, or to leave.

6. You have travelled to Haiti, New Orleans and Afghanistan, just to name a few, is there a place that resonates in your heart?

All of those places resonate in my heart, but if I have to pick one it would be New Orleans, simply because of the amount of time I spent there and the number of human connections I made. The way the denizens of New Orleans were able to lift themselves up by their bootstraps and reclaim their city was a wonderful thing to witness. I hope my images do the place justice. I still go back whenever I can these days, usually for pleasure. I just returned from Jazzfest recently, it was great to see the city so buzzing and alive. But there is still an awful lot of work to be done down there.

7. Do you use different cameras to convey various emotions and messages? If so, which ones?

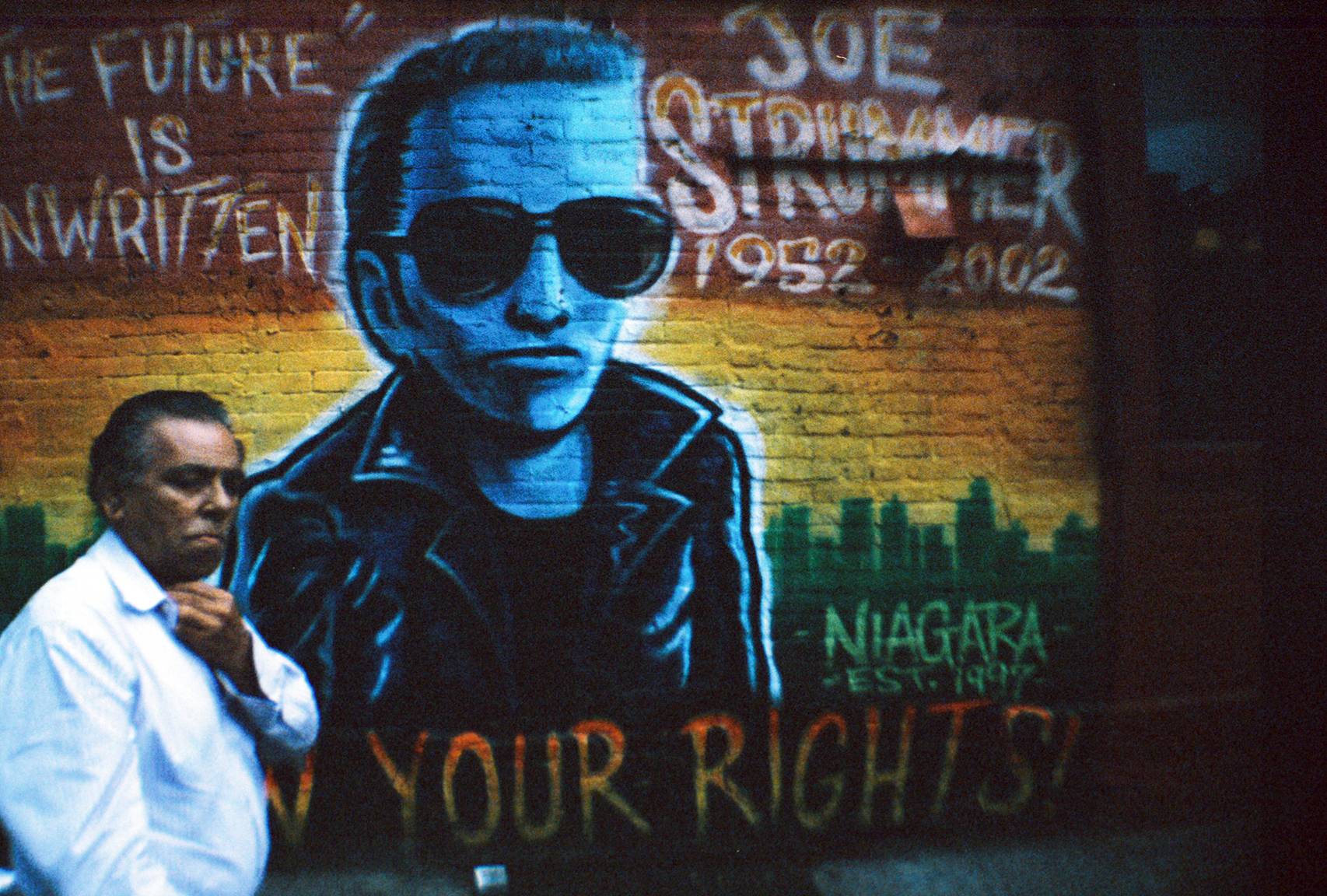

Almost everything I shoot for Getty Images is digital. The speed of the news cycle demands it for just about all we do, but I do occasionally have the opportunity to shoot film. One project I did in 2011 was entirely shot with the Lomo Sprocket Rocket. I shot an essay on the 10th anniversary of 9/11 on Tri-X. That was a lovely experience – the camera itself is such a beautiful little device to work with. The shutter is practically silent and it must weigh, what, a few ounces? My thought about using that camera was that it would be a perfect way to channel this 16-acre piece of real estate, the World Trade Center space, in a new way. At the time, the site was still a mostly empty, vast horizontal space in a city of verticality. I felt the wide format of the Sprocket Rocket would really capture properly the expanse of the space. I had photographed the place more than 100 times and needed a new way to look at it, a new methodology. I was able to shoot some candid moments down there that I probably couldn’t have gotten had I been lugging around my big digital cameras. I was able to blend in and just looked like another geeky tourist snapping pictures. No one noticed me at all. It was like being invisible, which is usually impossible for a photojournalist.

8. Tell us a little about your latest book Coming Back: New Orleans Resurgent. Why was this such a special project?

While I have witnessed war and disaster worldwide, there is something much more disturbing about seeing citizens from your own country basically abandoned by government. This experience penetrated my soul in a way that none of the others had, and I was staunchly compelled to document the folks of New Orleans and beyond as they attempted to rebuild their lives, to reconstruct their identities. I returned more than 15 times over the next five years to document the slow but steady revival of this incredible city. At Getty Images, we wanted to give something back, and so I was able to publish my book and we are donating 100 percent of our royalties to New Schools for New Orleans. Coming Back: New Orleans Resurgent is not just a document of the disaster itself, it is more importantly a portrait of a people who reclaimed their city.

9. Where would you like to shoot next? And why?

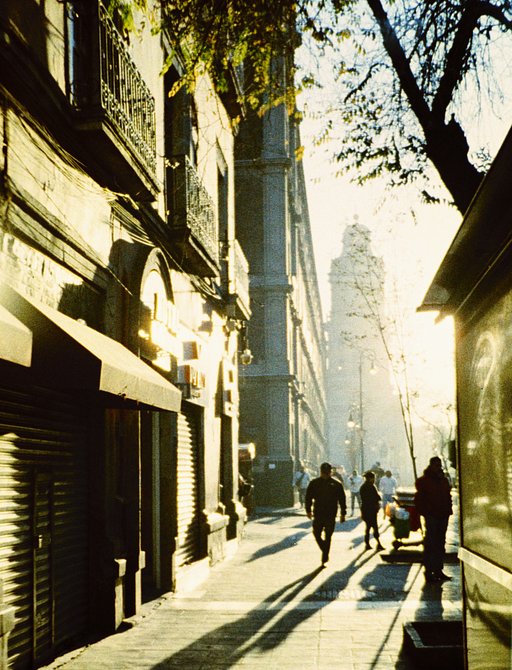

My last two overseas projects have been in Brazil and I hope to do a lot more work there, and in the rest of South America. The Amazon remains the vanguard frontline of the current environmental battles. Brazil is poised to be a force that will shape how the world evolves and I find that incredibly interesting. In some ways Brazil seems like America in 1900, loaded with natural resources and optimism, and still finding its footing on the international stage. With the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics coming to Brazil, eyes will be focused South. In addition, the mixture of slave trade histories and cultural identities remind me a lot of New Orleans, so it is in some way a natural extension of my last project.

I’m also fascinated by Senegal, which has a lot of cultural, musical and spiritual links to New Orleans, also via the slave trade. I hope to explore these links someday. But for now, you’ll hopefully find me in South America.

10. Lastly, what advice would you give to aspiring photojournalists?

The market is changing and most photojournalists will tell you photojournalism is in a decline as a profession. Print media is weakening and there simply isn’t as much work out there as there was previously. This is combined with the fact that journalism schools are still producing new photojournalists every year, who are all hungry for work. If you want to be a photojournalist you have to be extremely cognizant of this reality. That said, the best proving ground for photojournalists remains starting at a local newspaper to hone your skills. If you can find an internship at a decent local paper, even if it doesn’t pay, this will be the quickest way to develop your skills. There are also multimedia/photo editing internships at news websites and wire services.

If you’re going to make it, talent is only one factor. You’re going to need to truly love it. The work is often grueling, you’re away from home, away from family. It is often difficult to maintain relationships. It is really a lifelong commitment if you’re serious. This isn’t a profession you choose, it chooses you.

Thank you Mario! Safe travels!

—

For more of Mario’s work visit his website, follow him on Twitter and on Facebook

written by arianececilia on 2013-05-15 #people #art #lomo-amigo #analogue-photography #photographer #lomography #features #analogue-cameras #photojournalism #coverage #lomoamigo #getty-images #mario-tama

No Comments